Annie Leonard returns with Season 2 of The Story of Stuff! Watch her new movie, The Story of Broke: Why There's Still Plenty of Money to Build a Better Future, to bust the myth that the United States is broke. Annie talks about corporate tax loopholes, enormous tax breaks for the richest 1%, and military spending, and then she breaks down the different types of subsidies that the government hands out to big businesses - all of which give the impression that the country is too broke to build a healthy, green economy. My hope is that this information helps us realize that we can't keep electing the wrong people, people who will only continue this disastrous trend that offers such a bleak future for the generations to come. Please share this video with your friends and family!

Showing posts with label subsidies. Show all posts

Showing posts with label subsidies. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Eric Schlosser explains why being a foodie isn't "elitist"

I'm out of town for part of this week, so instead of writing I thought I might share a great article from the Washington Post with you. It's long compared to my usual posts but well worth the read. It touches on so many issues within our broken food system that have caused me to put food and agricultural issues at the top of my list of environmental concerns.

At the American Farm Bureau Federation's annual meeting this year, Bob Stallman, the group's president, lashed out at "self-appointed food elitists" who are "hell-bent on misleading consumers." His target was the growing movement that calls for sustainable farming practices and questions the basic tenets of large-scale industrial agriculture in America.

The "elitist" epithet is a familiar line of attack. In the decade since my book "Fast Food Nation" was published, I've been called not only an elitist, but also a socialist, a communist and un-American. In 2009, the documentary "Food, Inc.," directed by Robby Kenner, was described as "elitist foodie propaganda" by a prominent corporate lobbyist. Nutritionist Marion Nestle has been called a "food fascist," while an attempt was recently made to cancel a university appearance by Michael Pollan, author of "The Omnivore's Dilemma," who was accused of being an "anti-agricultural" elitist by a wealthy donor.

This name-calling is a form of misdirection, an attempt to evade a serious debate about U.S. agricultural policies. And it gets the elitism charge precisely backward. America's current system of food production - overly centralized and industrialized, overly controlled by a handful of companies, overly reliant on monocultures, pesticides, chemical fertilizers, chemical additives, genetically modified organisms, factory farms, government subsidies and fossil fuels - is profoundly undemocratic. It is one more sign of how the few now rule the many. And it's inflicting tremendous harm on American farmers, workers and consumers.

During the past 40 years, our food system has changed more than in the previous 40,000 years. Genetically modified corn and soybeans, cloned animals, McNuggets - none of these technological marvels existed in 1970. The concentrated economic power now prevalent in U.S. agriculture didn't exist, either. For example, in 1970 the four largest meatpacking companies slaughtered about 21 percent of America's cattle; today the four largest companies slaughter about 85 percent. The beef industry is more concentrated now than it was in 1906, when Upton Sinclair published "The Jungle" and criticized the unchecked power of the "Beef Trust." The markets for pork, poultry, grain, farm chemicals and seeds have also become highly concentrated.

America's ranchers and farmers are suffering from this lack of competition for their goods. In 1970, farmers received about 32 cents for every consumer dollar spent on food; today they get about 16 cents. The average farm household now earns about 87 percent of its income from non-farm sources.

While small farmers and their families have been forced to take second jobs just to stay on their land, wealthy farmers have received substantial help from the federal government. Between 1995 and 2009, about $250 billion in federal subsidies was given directly to American farmers - and about three-quarters of that money was given to the wealthiest 10 percent. Those are the farmers whom the Farm Bureau represents, the ones attacking "big government" and calling the sustainability movement elitist.

Food industry workers are also bearing the brunt of the system's recent changes. During the 1970s, meatpackers were among America's highest-paid industrial workers; today they are among the lowest paid. Thanks to the growth of fast-food chains, the wages of restaurant workers have fallen, too. The restaurant industry has long been the largest employer of minimum-wage workers. Since 1968, thanks in part to the industry's lobbying efforts, the real value of the minimum wage has dropped by 29 percent.

Migrant farmworkers have been hit especially hard. They pick the fresh fruits and vegetables considered the foundation of a healthy diet, but they are hardly well-rewarded for their back-breaking labor. The wages of some migrants, adjusted for inflation, have dropped by more than 50 percent since the late 1970s. Many grape-pickers in California now earn less than their counterparts did a generation ago, when misery in the fields inspired Cesar Chavez to start the United Farm Workers Union.

While workers are earning less, consumers are paying for this industrial food system with their health. Young children, the poor and people of color are being harmed the most. During the past 40 years, the obesity rate among American preschoolers has doubled. Among children ages 6 to 11, it has tripled. Obesity has been linked to asthma, cancer, heart disease and diabetes, among other ailments. Two-thirds of American adults are obese or overweight, and economists from Cornell and Lehigh universities have estimated that obesity is now responsible for 17 percent of the nation's annual medical costs, or roughly $168 billion.

African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic whites, and more likely to be poor. As upper-middle-class consumers increasingly seek out healthier foods, fast-food chains are targeting low-income minority communities - much like tobacco companies did when wealthy and well-educated people began to quit smoking.

Some aspects of today's food movement do smack of elitism, and if left unchecked they could sideline the movement or make it irrelevant. Consider the expensive meals and obscure ingredients favored by a number of celebrity chefs, the snobbery that often oozes from restaurant connoisseurs, and the obsessive interest in exotic cooking techniques among a certain type of gourmand.

Those things may be irritating. But they generally don't sicken or kill people. And our current industrial food system does.

Just last month, a study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases found that nearly half of the beef, chicken, pork and turkey at supermarkets nationwide may be contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. About 80 percent of the antibiotics in the United States are currently given to livestock, simply to make the animals grow faster or to prevent them from becoming sick amid the terribly overcrowded conditions at factory farms. In addition to antibiotic-resistant germs, a wide variety of other pathogens are being spread by this centralized and industrialized system for producing meat.

Children under age 4 are the most vulnerable to food-borne pathogens and to pesticide residues in food. According to a report by Georgetown University and the Pew Charitable Trusts, the annual cost of food-borne illness in the United States is about $152 billion. That figure does not include the cost of the roughly 20,000 annual deaths from antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

One of the goals of the Farm Bureau Federation is to influence public opinion. In addition to denying the threat of global warming and attacking the legitimacy of federal environmental laws, the Farm Bureau recently created an entity called the U.S. Farmers and Ranchers Alliance to "enhance public trust in our food supply." Backed by a long list of powerful trade groups, the alliance also plans to "serve as a resource to food companies" seeking to defend current agricultural practices.

But despite their talk of openness and trust, the giants of the food industry rarely engage in public debate with their critics. Instead they rely on well-paid surrogates - or they file lawsuits. In 1990, McDonald's sued a small group called London Greenpeace for criticizing the chain's food, starting a legal battle that lasted 15 years. In 1996, Texas cattlemen sued Oprah Winfrey for her assertion that mad cow disease might have come to the United States, and kept her in court for six years. Thirteen states passed "veggie libel laws" during the 1990s to facilitate similar lawsuits. Although the laws are unconstitutional, they remain on the books and serve their real purpose: to intimidate critics of industrial food.

In the same spirit of limiting public awareness, companies such as Monsanto and Dow Chemical have blocked the labeling of genetically modified foods, while the meatpacking industry has prevented the labeling of milk and meat from cloned animals. If genetic modification and cloning are such wonderful things, why aren't companies eager to advertise the use of these revolutionary techniques?

The answer is that they don't want people to think about what they're eating. The survival of the current food system depends upon widespread ignorance of how it really operates. A Florida state senator recently introduced a bill making it a first-degree felony to take a photograph of any farm or processing plant - even from a public road - without the owner's permission. Similar bills have been introduced in Minnesota and Iowa, with support from Monsanto.

The cheapness of today's industrial food is an illusion, and the real cost is too high to pay. While the Farm Bureau Federation clings to an outdated mind-set, companies such as Wal-Mart, Danone, Kellogg's, General Mills and Compass have invested in organic, sustainable production. Insurance companies such as Kaiser Permanente are opening farmers markets in low-income communities. Whole Foods is demanding fair labor practices, while Chipotle promotes the humane treatment of farm animals. Urban farms are being planted by visionaries such as Milwaukee's Will Allen; the Coalition of Immokalee Workers is defending the rights of poor migrants; Restaurant Opportunities Centers United is fighting to improve the lives of food-service workers; and Alice Waters, Jamie Oliver and first lady Michelle Obama are pushing for healthier food in schools.

Calling these efforts elitist renders the word meaningless. The wealthy will always eat well. It is the poor and working people who need a new, sustainable food system more than anyone else. They live in the most polluted neighborhoods. They are exposed to the worst toxic chemicals on the job. They are sold the unhealthiest foods and can least afford the medical problems that result.

A food system based on poverty and exploitation will never be sustainable.

Eric Schlosser is the author of "Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal" and a co-producer of the Oscar-nominated documentary "Food, Inc."

© 2011 The Washington Post Company

--------------------

Thoughts? Reactions? Do you feel passionate or apathetic about this?

Why being a foodie isn't 'elitist'

By Eric Schlosser, Friday, April 29, 3:59 PM

At the American Farm Bureau Federation's annual meeting this year, Bob Stallman, the group's president, lashed out at "self-appointed food elitists" who are "hell-bent on misleading consumers." His target was the growing movement that calls for sustainable farming practices and questions the basic tenets of large-scale industrial agriculture in America.

The "elitist" epithet is a familiar line of attack. In the decade since my book "Fast Food Nation" was published, I've been called not only an elitist, but also a socialist, a communist and un-American. In 2009, the documentary "Food, Inc.," directed by Robby Kenner, was described as "elitist foodie propaganda" by a prominent corporate lobbyist. Nutritionist Marion Nestle has been called a "food fascist," while an attempt was recently made to cancel a university appearance by Michael Pollan, author of "The Omnivore's Dilemma," who was accused of being an "anti-agricultural" elitist by a wealthy donor.

This name-calling is a form of misdirection, an attempt to evade a serious debate about U.S. agricultural policies. And it gets the elitism charge precisely backward. America's current system of food production - overly centralized and industrialized, overly controlled by a handful of companies, overly reliant on monocultures, pesticides, chemical fertilizers, chemical additives, genetically modified organisms, factory farms, government subsidies and fossil fuels - is profoundly undemocratic. It is one more sign of how the few now rule the many. And it's inflicting tremendous harm on American farmers, workers and consumers.

During the past 40 years, our food system has changed more than in the previous 40,000 years. Genetically modified corn and soybeans, cloned animals, McNuggets - none of these technological marvels existed in 1970. The concentrated economic power now prevalent in U.S. agriculture didn't exist, either. For example, in 1970 the four largest meatpacking companies slaughtered about 21 percent of America's cattle; today the four largest companies slaughter about 85 percent. The beef industry is more concentrated now than it was in 1906, when Upton Sinclair published "The Jungle" and criticized the unchecked power of the "Beef Trust." The markets for pork, poultry, grain, farm chemicals and seeds have also become highly concentrated.

America's ranchers and farmers are suffering from this lack of competition for their goods. In 1970, farmers received about 32 cents for every consumer dollar spent on food; today they get about 16 cents. The average farm household now earns about 87 percent of its income from non-farm sources.

While small farmers and their families have been forced to take second jobs just to stay on their land, wealthy farmers have received substantial help from the federal government. Between 1995 and 2009, about $250 billion in federal subsidies was given directly to American farmers - and about three-quarters of that money was given to the wealthiest 10 percent. Those are the farmers whom the Farm Bureau represents, the ones attacking "big government" and calling the sustainability movement elitist.

Food industry workers are also bearing the brunt of the system's recent changes. During the 1970s, meatpackers were among America's highest-paid industrial workers; today they are among the lowest paid. Thanks to the growth of fast-food chains, the wages of restaurant workers have fallen, too. The restaurant industry has long been the largest employer of minimum-wage workers. Since 1968, thanks in part to the industry's lobbying efforts, the real value of the minimum wage has dropped by 29 percent.

Migrant farmworkers have been hit especially hard. They pick the fresh fruits and vegetables considered the foundation of a healthy diet, but they are hardly well-rewarded for their back-breaking labor. The wages of some migrants, adjusted for inflation, have dropped by more than 50 percent since the late 1970s. Many grape-pickers in California now earn less than their counterparts did a generation ago, when misery in the fields inspired Cesar Chavez to start the United Farm Workers Union.

While workers are earning less, consumers are paying for this industrial food system with their health. Young children, the poor and people of color are being harmed the most. During the past 40 years, the obesity rate among American preschoolers has doubled. Among children ages 6 to 11, it has tripled. Obesity has been linked to asthma, cancer, heart disease and diabetes, among other ailments. Two-thirds of American adults are obese or overweight, and economists from Cornell and Lehigh universities have estimated that obesity is now responsible for 17 percent of the nation's annual medical costs, or roughly $168 billion.

African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic whites, and more likely to be poor. As upper-middle-class consumers increasingly seek out healthier foods, fast-food chains are targeting low-income minority communities - much like tobacco companies did when wealthy and well-educated people began to quit smoking.

Some aspects of today's food movement do smack of elitism, and if left unchecked they could sideline the movement or make it irrelevant. Consider the expensive meals and obscure ingredients favored by a number of celebrity chefs, the snobbery that often oozes from restaurant connoisseurs, and the obsessive interest in exotic cooking techniques among a certain type of gourmand.

Those things may be irritating. But they generally don't sicken or kill people. And our current industrial food system does.

Just last month, a study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases found that nearly half of the beef, chicken, pork and turkey at supermarkets nationwide may be contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. About 80 percent of the antibiotics in the United States are currently given to livestock, simply to make the animals grow faster or to prevent them from becoming sick amid the terribly overcrowded conditions at factory farms. In addition to antibiotic-resistant germs, a wide variety of other pathogens are being spread by this centralized and industrialized system for producing meat.

Children under age 4 are the most vulnerable to food-borne pathogens and to pesticide residues in food. According to a report by Georgetown University and the Pew Charitable Trusts, the annual cost of food-borne illness in the United States is about $152 billion. That figure does not include the cost of the roughly 20,000 annual deaths from antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

One of the goals of the Farm Bureau Federation is to influence public opinion. In addition to denying the threat of global warming and attacking the legitimacy of federal environmental laws, the Farm Bureau recently created an entity called the U.S. Farmers and Ranchers Alliance to "enhance public trust in our food supply." Backed by a long list of powerful trade groups, the alliance also plans to "serve as a resource to food companies" seeking to defend current agricultural practices.

But despite their talk of openness and trust, the giants of the food industry rarely engage in public debate with their critics. Instead they rely on well-paid surrogates - or they file lawsuits. In 1990, McDonald's sued a small group called London Greenpeace for criticizing the chain's food, starting a legal battle that lasted 15 years. In 1996, Texas cattlemen sued Oprah Winfrey for her assertion that mad cow disease might have come to the United States, and kept her in court for six years. Thirteen states passed "veggie libel laws" during the 1990s to facilitate similar lawsuits. Although the laws are unconstitutional, they remain on the books and serve their real purpose: to intimidate critics of industrial food.

In the same spirit of limiting public awareness, companies such as Monsanto and Dow Chemical have blocked the labeling of genetically modified foods, while the meatpacking industry has prevented the labeling of milk and meat from cloned animals. If genetic modification and cloning are such wonderful things, why aren't companies eager to advertise the use of these revolutionary techniques?

The answer is that they don't want people to think about what they're eating. The survival of the current food system depends upon widespread ignorance of how it really operates. A Florida state senator recently introduced a bill making it a first-degree felony to take a photograph of any farm or processing plant - even from a public road - without the owner's permission. Similar bills have been introduced in Minnesota and Iowa, with support from Monsanto.

The cheapness of today's industrial food is an illusion, and the real cost is too high to pay. While the Farm Bureau Federation clings to an outdated mind-set, companies such as Wal-Mart, Danone, Kellogg's, General Mills and Compass have invested in organic, sustainable production. Insurance companies such as Kaiser Permanente are opening farmers markets in low-income communities. Whole Foods is demanding fair labor practices, while Chipotle promotes the humane treatment of farm animals. Urban farms are being planted by visionaries such as Milwaukee's Will Allen; the Coalition of Immokalee Workers is defending the rights of poor migrants; Restaurant Opportunities Centers United is fighting to improve the lives of food-service workers; and Alice Waters, Jamie Oliver and first lady Michelle Obama are pushing for healthier food in schools.

Calling these efforts elitist renders the word meaningless. The wealthy will always eat well. It is the poor and working people who need a new, sustainable food system more than anyone else. They live in the most polluted neighborhoods. They are exposed to the worst toxic chemicals on the job. They are sold the unhealthiest foods and can least afford the medical problems that result.

A food system based on poverty and exploitation will never be sustainable.

Eric Schlosser is the author of "Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal" and a co-producer of the Oscar-nominated documentary "Food, Inc."

© 2011 The Washington Post Company

--------------------

Thoughts? Reactions? Do you feel passionate or apathetic about this?

Sunday, March 6, 2011

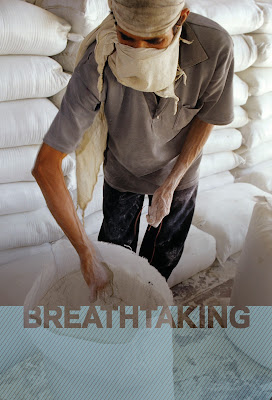

Breathtaking, but not Silencing

Asbestos is a carcinogen. The Canadian government has banned its use in construction materials for homes and is spending millions to remove it from the Parliament buildings. Then why are we exporting it to developing countries? This is the question Kathleen Mullen sought to answer in her investigative documentary about the historical and present-day use of asbestos in Canada and abroad. After losing her father, Richard Mullen, to mesothelioma (a cancer caused by exposure to asbestos), Mullen travelled to Quebec, India, and Detroit to tell the story of this powerful carcinogen and the people it harms.

On February 24th, I was lucky enough to attend the Toronto premiere of Breathtaking, co-presented by Planet in Focus (I was volunteering as box office staff on the night of the screening). At the beginning of the evening, I was excited to watch a documentary about a substance that I first heard about as a child when it had to be removed from the ceiling of my primary school; by the end of the night, I was deeply saddened by the number of lives affected by asbestos and outraged by the part we as Canadians play in this avoidable suffering.

The film opens with reflections on Richard Mullen's work and family life set to still images and Super 8 video of the Mullen family. His wife Sheila explains that he worked for some years in Aruba as an engineer for an oil company. As part of his job, he would inspect pipes that could only be accessed by opening the surrounding insulation which contained asbestos. Decades later, the fibres that had come to settle into the lining of his lungs as a result of this exposure ultimately caused his mesothelioma.

Inspired to learn all that she can about what ended her father's life, Kathleen Mullen begins her investigations in Quebec, where the only remaining Canadian asbestos mines are still in operation. It is due to these mines that Canada is one of the world's biggest producers of asbestos, specifically the chrysotile type. When health concerns grew and Canada began to restrict the use of asbestos, the industry saved itself by exporting its products to developing countries in which the substance has not been banned. Meanwhile, those living near the mines question whether they will get sick from inhaling airborne fibres as they blow off of nearby mine tailings. They are outnumbered, however, by those who believe chrysotile to be the safest type of asbestos that, when mined properly, is said to pose no risk to workers or the community. I believe that history, pride, and propaganda play no small role in the beliefs held by residents of small industrial towns.

Mullen also travels with her sister Anne-Mary to India, one of the countries that buys Canadian asbestos. In New Delhi, they speak with activists trying to lobby the government to ban its use in piping (for sanitary drains, irrigation, and even the water supply) and for low-cost housing. Then, in the industrial city of Ahmedabad, they meet sick factory workers fighting for compensation from companies who refuse to admit that the employees' exposure to asbestos is in any way unsafe. Many of those who develop asbestos-related cancers in India are too poor to be able to afford treatment and die without medical follow-up in their homes.

In Detroit, Mullen attends an Asbestos Awareness Conference. One of the speakers explains that he lost both of his parents to asbestos-related cancers and that he and his four brothers carry asbestos fibres in the linings of their lungs. When entire families can get sick despite only one family member working in a factory that manufactures products using asbestos, we have to ask ourselves whether there is such a thing as a safe level of exposure.

The documentary ends with three disheartening facts: more than 40 countries have banned asbestos, including the entire European Union - but not Canada or the United States. The Canadian and Quebec governments spend half a million (of our) dollars per year funding the Chrysotile Institute, a registered asbestos lobby group. And the World Health Organization estimates that over 90,000 people die every year of asbestos-related cancers.

By interspersing scenes of her journey with images and home movies of her family, footage of her father providing testimony of his work and illness for a lawsuit against his former employers, and facts about asbestos and its use, Mullen has created a film that is simultaneously a personal story, an investigative documentary, and a political statement. She weaves these elements together as though they are inseparable; and in a way, we can't get the whole picture without taking each perspective. Breathtaking moved my heart, informed my brain, and provoked the activist in me.

A panel discussion followed the screening. Moderator Alec Farquhar, Managing Director of the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW), introduced the panelists:

Many interesting points were raised both during the panel discussion and later, when audience members were invited to share their comments. I will not repeat them here, as this post is already very long, but you can imagine that many agreed that the asbestos industry is unethical and adds more stains to Canada's somewhat tarnished environmental reputation (tar sands, anyone?). Tensions ran particularly high when an asbestos industry representative went up to the microphone to say a few words. To his credit, his statement was well-written and delivered with sensitivity. Besides acknowledging that the deaths caused by exposure to asbestos are tragic and that unsafe handling of the substance must come to an end, the industry representative invited the audience to consider whether developing countries continue to buy asbestos because it meets the needs of their economy, and that this could explain why the Supreme Court of India refused to ban asbestos. What do you think?

This is a challenging issue with no simple solutions. Nevertheless, I, for one, would prefer for my tax dollars to support research into safe and affordable alternatives to asbestos and the re-education of Canadian asbestos miners to start new careers - not subsidies for the asbestos industry.

Stay tuned for my next blog post: an interview with Director Kathleen Mullen. For more information and to organize a screening in your community, please contact breathtakingfilm (at) gmail.com or visit Kathleen Mullen's website.

|

| Photo credit: P. Madhavan |

On February 24th, I was lucky enough to attend the Toronto premiere of Breathtaking, co-presented by Planet in Focus (I was volunteering as box office staff on the night of the screening). At the beginning of the evening, I was excited to watch a documentary about a substance that I first heard about as a child when it had to be removed from the ceiling of my primary school; by the end of the night, I was deeply saddened by the number of lives affected by asbestos and outraged by the part we as Canadians play in this avoidable suffering.

The film opens with reflections on Richard Mullen's work and family life set to still images and Super 8 video of the Mullen family. His wife Sheila explains that he worked for some years in Aruba as an engineer for an oil company. As part of his job, he would inspect pipes that could only be accessed by opening the surrounding insulation which contained asbestos. Decades later, the fibres that had come to settle into the lining of his lungs as a result of this exposure ultimately caused his mesothelioma.

Inspired to learn all that she can about what ended her father's life, Kathleen Mullen begins her investigations in Quebec, where the only remaining Canadian asbestos mines are still in operation. It is due to these mines that Canada is one of the world's biggest producers of asbestos, specifically the chrysotile type. When health concerns grew and Canada began to restrict the use of asbestos, the industry saved itself by exporting its products to developing countries in which the substance has not been banned. Meanwhile, those living near the mines question whether they will get sick from inhaling airborne fibres as they blow off of nearby mine tailings. They are outnumbered, however, by those who believe chrysotile to be the safest type of asbestos that, when mined properly, is said to pose no risk to workers or the community. I believe that history, pride, and propaganda play no small role in the beliefs held by residents of small industrial towns.

Mullen also travels with her sister Anne-Mary to India, one of the countries that buys Canadian asbestos. In New Delhi, they speak with activists trying to lobby the government to ban its use in piping (for sanitary drains, irrigation, and even the water supply) and for low-cost housing. Then, in the industrial city of Ahmedabad, they meet sick factory workers fighting for compensation from companies who refuse to admit that the employees' exposure to asbestos is in any way unsafe. Many of those who develop asbestos-related cancers in India are too poor to be able to afford treatment and die without medical follow-up in their homes.

In Detroit, Mullen attends an Asbestos Awareness Conference. One of the speakers explains that he lost both of his parents to asbestos-related cancers and that he and his four brothers carry asbestos fibres in the linings of their lungs. When entire families can get sick despite only one family member working in a factory that manufactures products using asbestos, we have to ask ourselves whether there is such a thing as a safe level of exposure.

The documentary ends with three disheartening facts: more than 40 countries have banned asbestos, including the entire European Union - but not Canada or the United States. The Canadian and Quebec governments spend half a million (of our) dollars per year funding the Chrysotile Institute, a registered asbestos lobby group. And the World Health Organization estimates that over 90,000 people die every year of asbestos-related cancers.

By interspersing scenes of her journey with images and home movies of her family, footage of her father providing testimony of his work and illness for a lawsuit against his former employers, and facts about asbestos and its use, Mullen has created a film that is simultaneously a personal story, an investigative documentary, and a political statement. She weaves these elements together as though they are inseparable; and in a way, we can't get the whole picture without taking each perspective. Breathtaking moved my heart, informed my brain, and provoked the activist in me.

A panel discussion followed the screening. Moderator Alec Farquhar, Managing Director of the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW), introduced the panelists:

- Kathleen Mullen

- Sheila Mullen

- Anne-Mary Mullen

- Dr. Pravesh Jugnundan: occupational health physician, consultant to OHCOW, and member of the Occupational and Environmental Medical Association of Canada (OEMAC) Board of Directors

- Lyle Hargrove: Director of the Canadian Auto Workers Health and Safety Training Fund and member of the OHCOW Board of Directors

- Dorothy Goldin Rosenberg: researcher and producer of the documentary film Toxic Trespass, Environmental Health professor at the University of Toronto, and affiliate of the Women's Healthy Environments Network and the Toronto Cancer Prevention Coalition.

Many interesting points were raised both during the panel discussion and later, when audience members were invited to share their comments. I will not repeat them here, as this post is already very long, but you can imagine that many agreed that the asbestos industry is unethical and adds more stains to Canada's somewhat tarnished environmental reputation (tar sands, anyone?). Tensions ran particularly high when an asbestos industry representative went up to the microphone to say a few words. To his credit, his statement was well-written and delivered with sensitivity. Besides acknowledging that the deaths caused by exposure to asbestos are tragic and that unsafe handling of the substance must come to an end, the industry representative invited the audience to consider whether developing countries continue to buy asbestos because it meets the needs of their economy, and that this could explain why the Supreme Court of India refused to ban asbestos. What do you think?

This is a challenging issue with no simple solutions. Nevertheless, I, for one, would prefer for my tax dollars to support research into safe and affordable alternatives to asbestos and the re-education of Canadian asbestos miners to start new careers - not subsidies for the asbestos industry.

Stay tuned for my next blog post: an interview with Director Kathleen Mullen. For more information and to organize a screening in your community, please contact breathtakingfilm (at) gmail.com or visit Kathleen Mullen's website.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)