|

| Photo credit: P. Madhavan |

On February 24th, I was lucky enough to attend the Toronto premiere of Breathtaking, co-presented by Planet in Focus (I was volunteering as box office staff on the night of the screening). At the beginning of the evening, I was excited to watch a documentary about a substance that I first heard about as a child when it had to be removed from the ceiling of my primary school; by the end of the night, I was deeply saddened by the number of lives affected by asbestos and outraged by the part we as Canadians play in this avoidable suffering.

The film opens with reflections on Richard Mullen's work and family life set to still images and Super 8 video of the Mullen family. His wife Sheila explains that he worked for some years in Aruba as an engineer for an oil company. As part of his job, he would inspect pipes that could only be accessed by opening the surrounding insulation which contained asbestos. Decades later, the fibres that had come to settle into the lining of his lungs as a result of this exposure ultimately caused his mesothelioma.

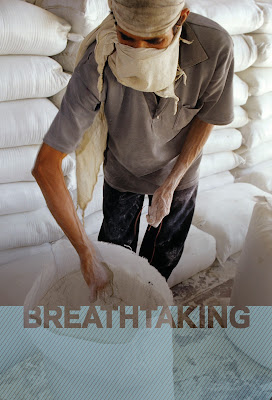

Inspired to learn all that she can about what ended her father's life, Kathleen Mullen begins her investigations in Quebec, where the only remaining Canadian asbestos mines are still in operation. It is due to these mines that Canada is one of the world's biggest producers of asbestos, specifically the chrysotile type. When health concerns grew and Canada began to restrict the use of asbestos, the industry saved itself by exporting its products to developing countries in which the substance has not been banned. Meanwhile, those living near the mines question whether they will get sick from inhaling airborne fibres as they blow off of nearby mine tailings. They are outnumbered, however, by those who believe chrysotile to be the safest type of asbestos that, when mined properly, is said to pose no risk to workers or the community. I believe that history, pride, and propaganda play no small role in the beliefs held by residents of small industrial towns.

Mullen also travels with her sister Anne-Mary to India, one of the countries that buys Canadian asbestos. In New Delhi, they speak with activists trying to lobby the government to ban its use in piping (for sanitary drains, irrigation, and even the water supply) and for low-cost housing. Then, in the industrial city of Ahmedabad, they meet sick factory workers fighting for compensation from companies who refuse to admit that the employees' exposure to asbestos is in any way unsafe. Many of those who develop asbestos-related cancers in India are too poor to be able to afford treatment and die without medical follow-up in their homes.

In Detroit, Mullen attends an Asbestos Awareness Conference. One of the speakers explains that he lost both of his parents to asbestos-related cancers and that he and his four brothers carry asbestos fibres in the linings of their lungs. When entire families can get sick despite only one family member working in a factory that manufactures products using asbestos, we have to ask ourselves whether there is such a thing as a safe level of exposure.

The documentary ends with three disheartening facts: more than 40 countries have banned asbestos, including the entire European Union - but not Canada or the United States. The Canadian and Quebec governments spend half a million (of our) dollars per year funding the Chrysotile Institute, a registered asbestos lobby group. And the World Health Organization estimates that over 90,000 people die every year of asbestos-related cancers.

By interspersing scenes of her journey with images and home movies of her family, footage of her father providing testimony of his work and illness for a lawsuit against his former employers, and facts about asbestos and its use, Mullen has created a film that is simultaneously a personal story, an investigative documentary, and a political statement. She weaves these elements together as though they are inseparable; and in a way, we can't get the whole picture without taking each perspective. Breathtaking moved my heart, informed my brain, and provoked the activist in me.

A panel discussion followed the screening. Moderator Alec Farquhar, Managing Director of the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW), introduced the panelists:

- Kathleen Mullen

- Sheila Mullen

- Anne-Mary Mullen

- Dr. Pravesh Jugnundan: occupational health physician, consultant to OHCOW, and member of the Occupational and Environmental Medical Association of Canada (OEMAC) Board of Directors

- Lyle Hargrove: Director of the Canadian Auto Workers Health and Safety Training Fund and member of the OHCOW Board of Directors

- Dorothy Goldin Rosenberg: researcher and producer of the documentary film Toxic Trespass, Environmental Health professor at the University of Toronto, and affiliate of the Women's Healthy Environments Network and the Toronto Cancer Prevention Coalition.

Many interesting points were raised both during the panel discussion and later, when audience members were invited to share their comments. I will not repeat them here, as this post is already very long, but you can imagine that many agreed that the asbestos industry is unethical and adds more stains to Canada's somewhat tarnished environmental reputation (tar sands, anyone?). Tensions ran particularly high when an asbestos industry representative went up to the microphone to say a few words. To his credit, his statement was well-written and delivered with sensitivity. Besides acknowledging that the deaths caused by exposure to asbestos are tragic and that unsafe handling of the substance must come to an end, the industry representative invited the audience to consider whether developing countries continue to buy asbestos because it meets the needs of their economy, and that this could explain why the Supreme Court of India refused to ban asbestos. What do you think?

This is a challenging issue with no simple solutions. Nevertheless, I, for one, would prefer for my tax dollars to support research into safe and affordable alternatives to asbestos and the re-education of Canadian asbestos miners to start new careers - not subsidies for the asbestos industry.

Stay tuned for my next blog post: an interview with Director Kathleen Mullen. For more information and to organize a screening in your community, please contact breathtakingfilm (at) gmail.com or visit Kathleen Mullen's website.

No comments:

Post a Comment